East Timor, Timor Leste - Asia's youngest nationTroubled history

The state consists of two parts - one of which, oddly, is not in eastern Timor, but on the northwestern coast of the island. This enclave called Oecusi (Okusi) or also Ambenu, is where western powers, i.c. Portugal, first created a foothold on the island, in 1515. The Portuguese would rule large parts of the island, including the eastern tip, for some 400 years (essentially all those parts not in the hands of the Dutch, with whom they warred continuously). They amassed fortunes exporting sandalwood from the island till the stands were depleted in the early 1800s, then introduced coffee and sugar cane cultivation. During World War II Japanese troops occupied Timor, inviting an invasion by Dutch and Australian troops which led to the fierce Battle of Timor, focused on control of Dili, the capital, and its facilities, but also raged in the mountainous interior. The battle caused massive devastation and left 50.000 East Timorese dead. After the war, the UN decreed East Timor to be a non-self governing territory under Portuguese administration. The Portuguese, to their credit, made a serious attempt to rebuild the former colony, not by sending in colonial civil servants, but by making use of the traditional hierarchical structures of Timorese society. Although this enabled traditional culture to remain intact, riots and attacks on Portuguese posts indicated continued anti-colonial feelings on the part of the population. With the revolution of 1974 Portugal shook off its dictatorial rule by the Salazar clique, and in the general spirit of freedom decided to withdraw from all its former colonies, including East Timor. This precipitate departure led to a power vacuum from which neighbouring Indonesia, then ruled by general Suharto, hoped to benefit. In 1975 Indonesian forces invaded the area, the beginning of an occupation that would last nearly a quarter century - a period of great turbulence due to the fierce resistance of the East Timorese people, especially in East Timor proper, the Oecusi (Ambenu) enclave remaining relatively peaceful. The imprisonment of high profile resistance leaders such as Xanana Gusmão drew much international attention and condemnation. After the resignation of Suharto regime in 1999, a newly elected government came to power which decided that the situation in East Timor was untenable, as it was hurting Indonesia's international reputation. Freedom at lastIn 1999 an agreement was worked out between Indonesia and Portugal providing for a referendum among the East Timorese on two options: autonomy within the Republic of Indonesia, or full independence. The UN administered ballot showed nearly 80 per cent of the electorate in favour of full sovereignty - an outcome that clearly had not been expected by Indonesia. Xanana Gusmão was installed as Asia's youngest country's first president.

Peacekeepers, led by Australia, went in to restore order and were later replaced by UN forces. The sudden departure of Indonesian civil servants brought government institutions and economic management to a standstill, almost halving the gross domestic product, and effectively setting back the country's development more than a generation. In 2002 East Timor's independence was recognised by Portugal, and the República Democrática de Timor-Leste could join the United Nations as an independent country. Ikat textiles from East-Timor East-Timorese nobles from Dom Aleixo, Dili district, in ceremonial attire. Early 20th C. Photographer unknown.

The traditional role of ikat cloth in East-Timorese societyIn all of the different cultural groups of East-Timor ikat textiles play a similar societal role: design elements served as markers of descent and social status. Motifs were strictly prescribed and proscribed depending on regional origin and clan affiliation. Some motifs might be reserved for specific ceremonies, usually around life cycle events, other motifs were reserved for cloth to be worn by warriors, believed to protect them from harm and imbue them with the strength requisite for victory. Such extremely powerful cloths might be held privately, but often were kept in the clan's adat house, where they would be protected by the collective power of the ancestors. As on most Indonesian islands, the cloths are seen to increase in power with age, as their very survival in a hostile environment (climate, insects, wear and tear resulting from use) is seen as proof of their immanent power. There are four main areas of ikat production in East-Timor: Lautem (mainly Los Palos), Cova Lima, Marobo, and the enclave of Oecusi, also known as Ambenu.Though blankets for men are also made, the majority of the ikat textiles produced in East Timor, especially in the 'real' east, are sarongs, called tais, after the Tetum word for weaving. Those for men are called mane tais, those for women feto tais. The ikat technique is here called with the regional term futus. Tais are signifiers of ethnicity, and designs are specific to language groups. The motifs, as almost everywhere in the Indonesian archipelago, are never just decoration, but full of meaning - at least they used to be. They form a symbolic language that speaks of cultural and religious traditions. Every woman was expected to bring some of their own work to her marriage as a kind of bridewealth, but tais were also used in other ritual exchanges and burial ceremonies. This ritual role assured expert weavers a position of elevated status in their communities. Rarity caused by turbulence and religious fervourThe decades of turbulence, accompanied by sustained social dislocation, severely compromised the quality of textile production in the region.As a result, few weavers today can emulate the high quality work that was common, or at least not uncommon, in the past. The technical skills - especially the complex mud dyeing - have mostly disappeared. In some key areas, there are only two or three women left who still master the ancient techniques.This is a serious problem, but one that might be be overcome. Worse is that much of the knowledge of the traditional motifs and their meaning has been irretrievably lost. An exception is the remote Marobo region, where the transfer of traditional knowledge of dyeing and weaving is still being passed on to young women. The same turbulence no doubt also contributed to the paucity of East Timorese textiles in western hands, as the onset of Indonesian occupation neatly coincides with the awakening of interest in ikat, and the onset of active collecting. During the era of Indonesian occupation most dealers and collectors would have found it simply too dangerous to scour the interior for old textiles. Even if they had gone, it is doubtful that they would have found much. The Portuguese colonial overlords did not in general take much of an interest in the artifacts of the region, but their priests did. They saw the tais, correctly, as a vital manifestation of ancient Timorese customs and beliefs, central to a traditional 'pagan' life which, as elsewhere in the Indonesian archipelago often survived below a veneer of Christianity, and which they were determined to eradicate in order to save the souls of the natives - or enhance their own status in the church as ruthless destroyers of the devil's work. To that end, some of the more ambitious priests in the 1950s organized mass burnings of ritual tais, throwing onto the bonfires some of the best examples of ikat technique produced in the entire archipelago.

Ikat textiles from Lautem (Los Palos)Some of the artistically most interesting ikats come from the Lautem district, particularly the flatlands of Los Palos in the south east corner of the island, home to the Fataluku people. Their tais, which express their ancestral heritage, are revered and valued highly in traditional exchange, often being valued as the equivalent of several buffalo, the best as many as ten. Similarly, western collectors cannot expect to run into fine specimens for little money: for their enjoyment a serious offer must be made. But as they old saying goes, the pain of a high price diminishes rapidly over time, while the joy provided by quality tends to increase with time.Los Palos ikats in good condition are very rare. When Brigitte Khan Majlis showed a Los Palos tais in her Woven Messages in 1991, it was a première. Only a few more have since appeared in public. The three pieces in our collection therefore contribute significantly to our collective knowledge of these magnificent textiles.

Ikat textiles from Cova LimaThe ikat textiles from Cova Lima are of very intricate design, unequalled anywhere else in East-Timor. The social structure of the Fehan people who inhabit this coastal region in southwestern East Timor is matrilineal. This has facilitated the development and transfer to next generations of an extensive repertoire of complex motifs, especially for men's wraps, most of which are representative of clan membership. The geometric motifs are reminiscent of Indian trade textiles from the Coromandel Coast and Gujarat, including patola, which were brought to Timor by the Portuguese and the Dutch from the 16th C. onwards, or possibly earlier by traders of Asian, e.g. Arab, origin. These foreign cloths, with often highly complex design, must have impressed the islanders greatly, and were kept as treasure by the ruling elite, to be displayed to their greater glory at ceremonies and festivities. The general population was not allowed to copy such foreign motifs, as they were reserved for the nobility, but when the traditional power structures largely collapsed during the tumultuous 1970s, these restrictions could no longer be upheld, and motifs inspired by the ancient Indian trade cloths trickled into wider use. Their influence on Cova Lima ikat cloths is visible, but never dominant. Cova Lima ikat is rarely seen in Western collections, and rarely mentioned in literature .

Ikat textiles from Marobo and BobonaroThe ikat textiles from Bobonaro district, located in the remote, mountainous region on western East-Timor, are likely to represent one of the oldest continuous textile traditions of the Indonesian islands: certainly hundreds, when not thousands of years old. The ikat cloths, called utus in the local Kemak language, are made of hand spun locally grown cotton of a very fine quality, and are predominantly dark brown and black, tones that are achieved by mixing indigo with iron-rich mud and sometimes buffalo dung. They are decorated with a limited range of relatively simple motifs, such as squiggles and rows of dots. The best come from the hamlet of Marobo, which is blessed with hot springs, and an abundance of the requisite ferrous mud. Nowadays brighter, chemical dyes are also used, producing the usual tacky effect. The appearance of older Bobonaro utus to the contrary is sophisticated chic: sober and restrained. There are very few of them in western collections, and they rarely even figure in literature.

Ikat textiles from Oecusi (Ambenu) enclavePredictably, the ikat textiles from the Oecusi enclave, located as it is in Western Indonesian Timor, on the northern coast, show a great similarity to those from the surrounding region, also peopled by of Atoni stock. Actually, part of Ambenu, the coastal plains, is inhabited by people who originally came from Roti and Savu, and by Lamaholot from Flores and the Solor archipelago, but they arrived many centuries ago and by now speak the same Dawan language as the people from the mountainous interior and have similar traditions. Their ikats are decorated with motifs common in other parts of western Timor, such as crocodiles, the interlocking kaif motifs, jungle chicken, and other animals, and also with floral patterns derived from Portuguese examples. The region is less developed than surrounding Indonesian West-Timor, less influenced by modernity, and the creation ikat textiles made in the traditional manner, with hand spun cotton and vegetable dyes exclusively, survived longer, though the examples shown Yaeger and Jacobson, all made at least partly with chemical dyes, suggest that they are hard to find. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Literature

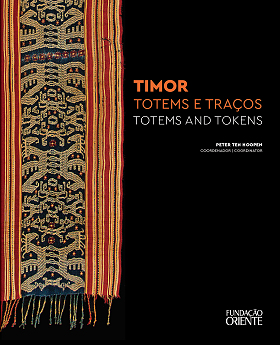

As of this writing in 2013, there is no monograph on the textiles of East Timor, but Fowlers's Textiles of Timor by Hamilton and Barrkman covers East Timor very well. The Oecusi (Ambenu) part of Timor-Leste, which is covered in Yeager and Jacobson's excellent Textiles of Western Timor. There is a web course on East Timor written for a general audience, Andrea K. Molnar's East Timor: An Introduction to the History, Politics and Culture of Southeast Asia's Youngest Nation which provides a good introduction. Highly recommended is The Art of Futus, a succint yet excellent introduction on the ikats of East Timor by the Alola Foundation.Apart from the titles mentioned above you may want to consider acquiring Peter ten Hoopen, ed., Timor: Totems and Tokens, which appeared in 2019. It gives an overview of different styles of ikat on Timor, using almost exclusively early examples, and is particularly strong on East Timor.

Map of East Timor - Timor-Leste

©Peter ten Hoopen, 2024. The contents of this website are provided for personal, educational, non-commercial use only.

No part of this website may be reproduced in any form without explicit permission of the copyright holder.