|

IKAT FROM FLORES GROUP, INDONESIA

GALLERY

- 007 PENINSULA

Kewatek (sarong). Warp ikat. Early 20th c. Ili Mandiri (most likely), Bama, Lewolaga, or Lobe Tobi. Due to great stylistic similarity exact provenance may be impossible to pin down.

- 021 LIO

Lawo (sarong). Warp ikat. 1930-1950. Nggela or nearby village

- 022 LIO

Lawo (sarong). Warp ikat. 1925-1950. Nggela or nearby village

- 024 SIKKA

Sarong. Warp ikat. 1925 or older. Identification of Sikka provenance is tentative. Another possibility is the area in Ende Regency north of Lio called Detusoko.

- 045 LIO

Lawo (sarong). Warp ikat. 1950. Nggela or a neighbouring village

- 050 SIKKA

Utang (sarong). Warp ikat. Circa 1950. Maumere area

- 051 SIKKA

Utang (sarong). Warp ikat. 1925-1945. Maumere area

- 052 NAGE KEO

Hoba (sarong). Warp ikat. 19th to early 20th c. Village unknown.

- 053 SIKKA

Utang (sarong). Warp ikat. 1930s. Welai village, Maumere area.

- 054 LIO

Semba (man's shawl). Warp ikat. 1950. Nggela.

- 055 LIO

Semba (man's shawl). Warp ikat. 1950 or before. Nggela.

- 056 LIO

Semba (man's shawl). Warp ikat. Early 20th c. Nggela.

- 076 NGADHA

Sapu jara (sarong). Warp ikat. Early 20th c. Also Ngada, or referred to by name of capital, Bajawa.

- 082 LIO

Lawo (sarong). Warp ikat. 1950. Nggela or nearby village.

- 083 NDONA

Semba (man's shawl). Warp ikat. 1935-1950. Village not identified.

- 084 NDONA

Semba (man's shawl). Warp ikat. 1930-1945. Village not identified.

- 085 NDONA

Lawo (sarong). Warp ikat. 1930-1940. Almost certainly Enlace.

- 090 NDONA

Semba (man's shawl). Warp ikat. Circa 1950. Village not identified.

- 093 SIKKA

Utang (sarong). Warp ikat. 1940 or earlier. Village not identified. Probably Maumere.

- 097 PENINSULA

Kewatek (sarong). Warp ikat. mid 20th c. Bama (or Ili Mandiri?) in Bird's Head Peninsula. Lamaholot people.

- 099 LIO

Lawo (sarong). Warp ikat. 1920-1940. Nggela or nearby village.

- 108 NAGE KEO

Sada (man's wrap). Warp ikat. 1900-1925. Village unknown.

- 116 NGADHA

Lue (blanket). Warp ikat. 19th to early 20th c. Probably Lopi Jo.

- 128 PENINSULA

Kewatek (sarong). Warp ikat. 1930-1950. Demo Pagang, near Bama (between Bama and Nobo in the Lewo Tobi area), Lamaholot people.

- 161 ENDE

Semba (man's shawl). Warp ikat. 1910-1930. Probably Ende proper.

- 164 NGADHA

Utang (sarong). Weft ikat. Early 20th c. Ngadha, probably, Ende being another possibility. Yet another possible locale is northern Lio region called Detusoko.

- 190 ENDE

Zawo (sarong). Weft ikat. Circa 1850 (well before 1888)

- 196 ENDE

Zawo (sarong). Warp ikat. Circa 1930. Village unknown.

- 197 NAGE KEO

Sada (men's wrap). Warp ikat. 1900-1925. Village unknown.

- 199 ENDE

Semba (man's shawl). Weft ikat. 19th - early 20th c. �

- 209 PALU'E

Tama (sarong). Warp ikat. 19th c. to very early 20th c. Palue (off Flores), probably. Caveat: origin not beyond doubt due to absence of true cognates with certified provenance.

- 211 PENINSULA

Kewatek (sarong). Warp ikat. 1945 or before. Ili Mandiri.

- 213 KROWE

Utang (sarong). Warp ikat. 1950-1960. One of a group of clans residing in the hills south of Maumere that are often refered to as Iwangée, though they themselves resent this. Krowe is not entirely appropriate either as the people identify only as inhabitants of their individual villages, but at least it is not a derogatory term.

- 233 ENDE

Zawo (sarong). Warp ikat. 1940 or before. Village unknown, but probably Ende proper.

- 238 ENDE

Semba (man's shawl). Warp ikat. 19th or early 20th c. (before 1930). Ende proper most likely,given the design's sophistication.

- 239 ENDE

Semba (man's shawl). Warp ikat. 19th or early 20th c. (before 1930). Ende proper, most likely, given the stature of the man for whom this was intended.

- 246 ENDE

Semba (man's shawl). Warp ikat. 1910-1930

- 251 ENDE

Semba (men's shawl). Warp ikat. Before 1950. Identification requires further research.

- 259 ENDE

Zawo (sarong). Warp ikat. 1910-1930. Probably Ende proper.

- 305 PALU'E

Tama (sarong). Warp ikat. 19th to early 20th c. Kéli domain, or allied Ndéo

Flores: centuries of power struggle

Flores, locally known as Nusa Bunga (Flower Island, after the Portuguese), is the central island of the Lesser Sunda Islands, an island arc that extends from Bali in the west till Timor in the East. It is a relatively narrow, 375 km long from west to east, in parts only 25 km wide, nowhere wider than 100 km - and spectacularly scenic. It has several great volcanoes, some of them active, is mostly covered in lush vegetation, and most of the fields are irrigated terraces built on the slopes of mountains, like those on Bali. The name Flores means 'flowers' in Portuguese, and it is not hard to see why the early explorers might have come up with this designation. And there was no local name to compete with: the islanders had no concept of the island as a whole, limited as they were in their knowledge of the world, which hardly extended beyond the next range of hills.

Flores, like Timor and several other islands in the archipelago, was long the subject of a power struggle between the Portuguese (who came first) and the Dutch (always close on their heels), with the various strongholds shifting hands multiple times. In 1846, the Dutch and Portuguese governments began negotiations to finally settle their respective claims, but when these still had not been completed five years later, the Portuguese governor of the region, facing financial collapse, decided to sell Flores and the Solor archipelago to the Dutch for a sum of 200,000 florins. Though he did this without consulting the government in Lisbon and was dismissed in disgrace, the agreement was not rescinded. A few years later Flores and the Solor islands were integrated into the Dutch East Indies. During World War II Flores suffered invasion by the Japanese, then in 1945 became a part of independent Indonesia.

While these tussles for power were going on, one force managed to maintain its hold on the island: the Dominican Order, which came over in 1613 when the Dutch attacked the Portuguese fort on Solor. Almost the entire population, led by the Dominicans, fled to Larantuka, a harbour town on the southeastern coast of Flores, and there established a flourishing community of mixed descent, called Larantuqueiros or Topasses, which dominated the sandalwood trade for 200 years. The Dominican Order managed to establish itself as the de facto ruler of the island and the Solor Archipelago, and remains a major factor in inter-island trade, finance and shipping.

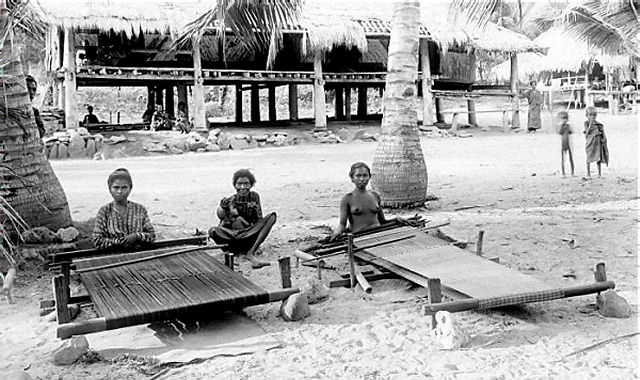

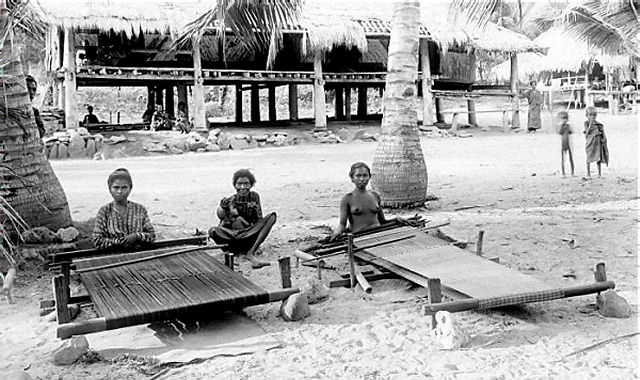

Women from the Sikka region in East Flores at their backstrap looms. Note a third weaver working under the floor of the longhouse. Photographer unknown, early 20th C. Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence.

Eight different worlds on one island

The Dutch colonisers - their missionaries forming the notable exception - dealt with the islanders almost exclusively through the various ports, and hardly developed the island's interior. They built only one road, not quite the length of the island, but much of it either never had asphalt or lost it over the years, mostly due to the heavy monsoon rains. Since independence little has been done to improve the infrastructure on Flores. Even these days, a road trip across the length of the island can easily take three days. This difficulty of road transport has caused the development of highly distinct cultures - separate little worlds really, very insular, like islands in an ocean of greenery - where different languages are spoken, different traditions are upheld, and artistic expression has taken on highly differentiated forms. The cloths from the Ngadha area for instance, with their primitive figurative decorations, are really worlds apart from the intricate, patola-inspired textiles from the nearby Lio district, and the Sikka cloths from the area near Maumere, are quite unlike those from Lobe Tobi, which lies in the shade of the same volcano. As far as ikat production is concerned there are seven main areas:

- Ende. Weaving concentrated in the South, around the island's capital. Produces fine ikat with notable patola influence, yet not as marked as in Lio and Ndona, and usually with a somewhat less impressive overall quality.

- Ndona. Lies a little to the east of Ende. Marked patola influence, excellent weaving.

- Ngadha. Region often referred to as Bajawa, after the main town. In south-central Flores. Primitive designs, mostly in white on indigo.

- Nage Keo. Combined name for the Nage and Keo areas in north-central Flores. Relatively simple designs, often with loose weaving.

- Lio. A little further south than Nage Keo. Marked patola influence, excellent weaving, among the very best in the archipelago.

- Sikka. Lies in the East, near Maumere. Some patola influence, also influence of European designs. Quality varies from middling to excellent.

- Peninsula. The 'Bird's Head Peninsula' near Larantuka in far eastern Flores (not to be confused with the eponymous peninsula in New Guinea) comprises two distinct weaving areas:

- Ili Mandiri. Older bridewealth cloths show patola influence. Those for daily wear have simple designs, mostly in white on indigo, created by patterns of white dots that are immediately recognizable.

- Lobe Tobi. In the extreme southeast of the island. Style related to Sikka and Ili Mandiri. Old bridewealth cloths found in only one western collection.

For more in-depth information on specific regions please click on the links above where available.

|

Literature

We are blessed with an excellent monograph on the textiles of Flores, Gift of the Cotton Maiden, edited by Roy Hamilton, with contributions by several known scholars. Most of the other books on the textiles of Indonesia have a section on Flores, and there are several good sources for those interested in the ethnology of the island's regions, notable among them Kent Watters article on Flores in Kahlenberg's Textile Traditions of Indonesia.

Map of Flores

Detailed maps of Flores by the US Army Map service in high resolution are found at the University of Texas:

©Peter ten Hoopen, 2024. The contents of this website are provided for personal, educational, non-commercial use only.

No part of this website may be reproduced in any form without explicit permission of the copyright holder.

|  |